margin: the white space between the text and the edges of the page

gutter: the inner margin

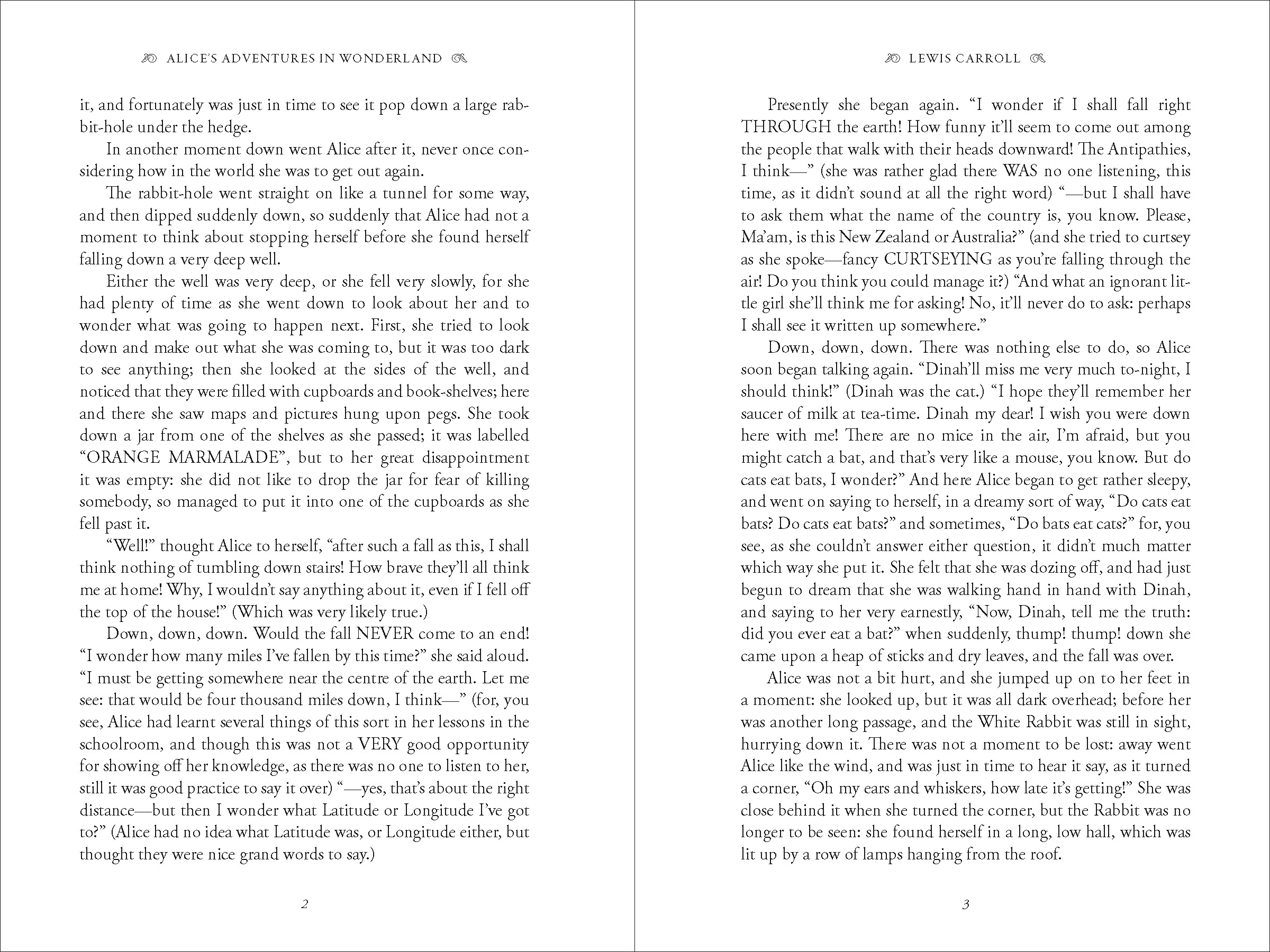

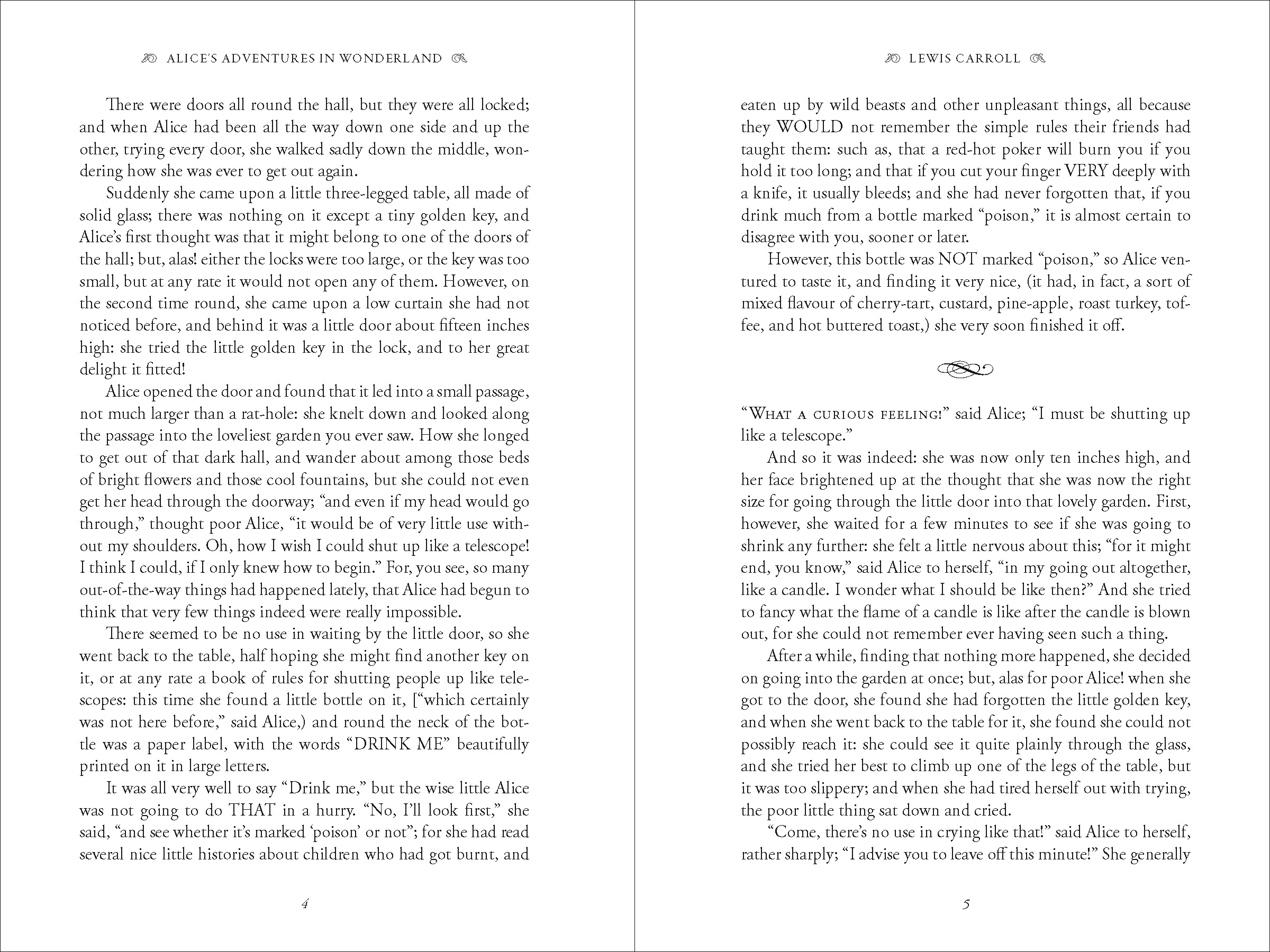

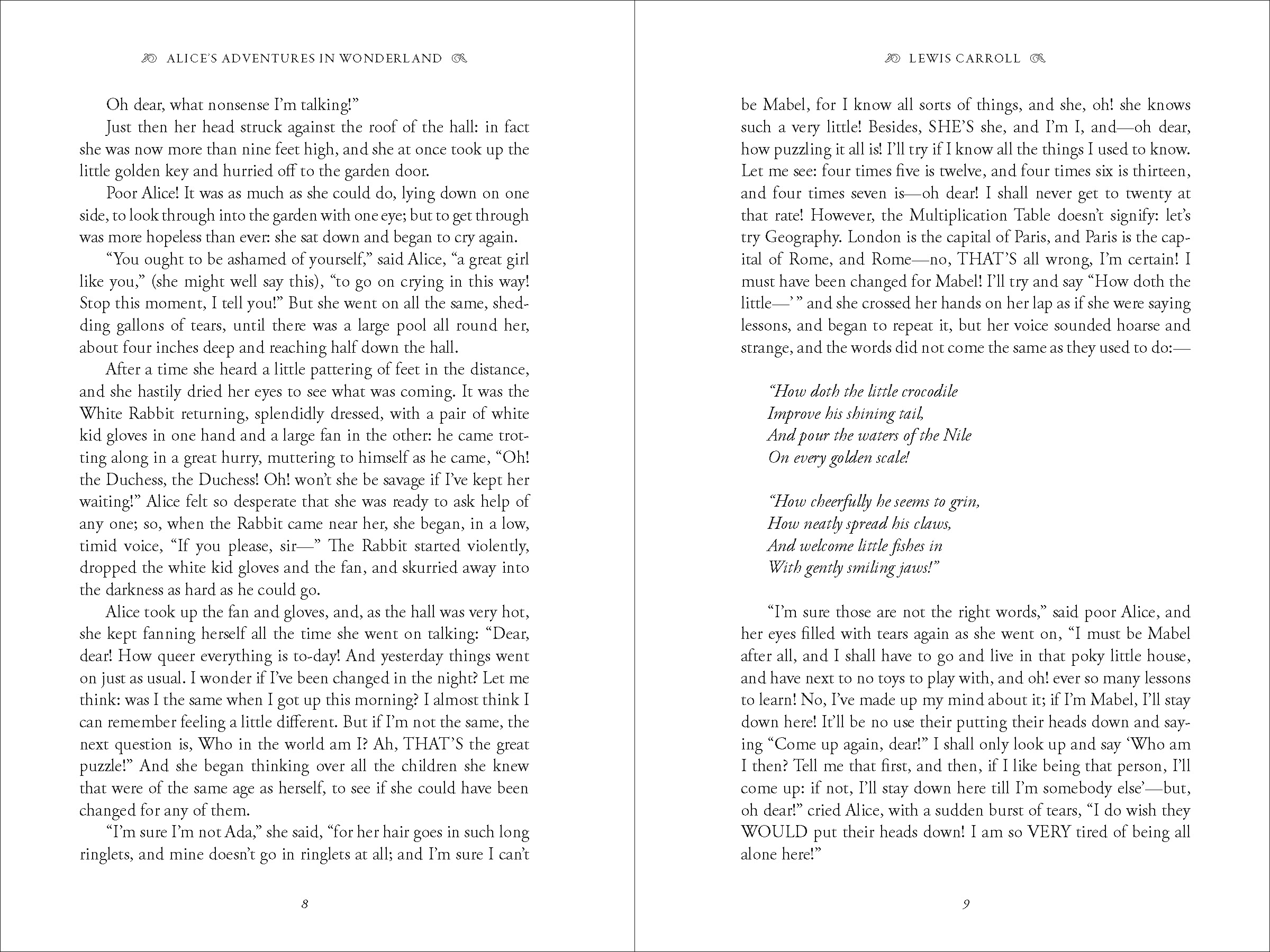

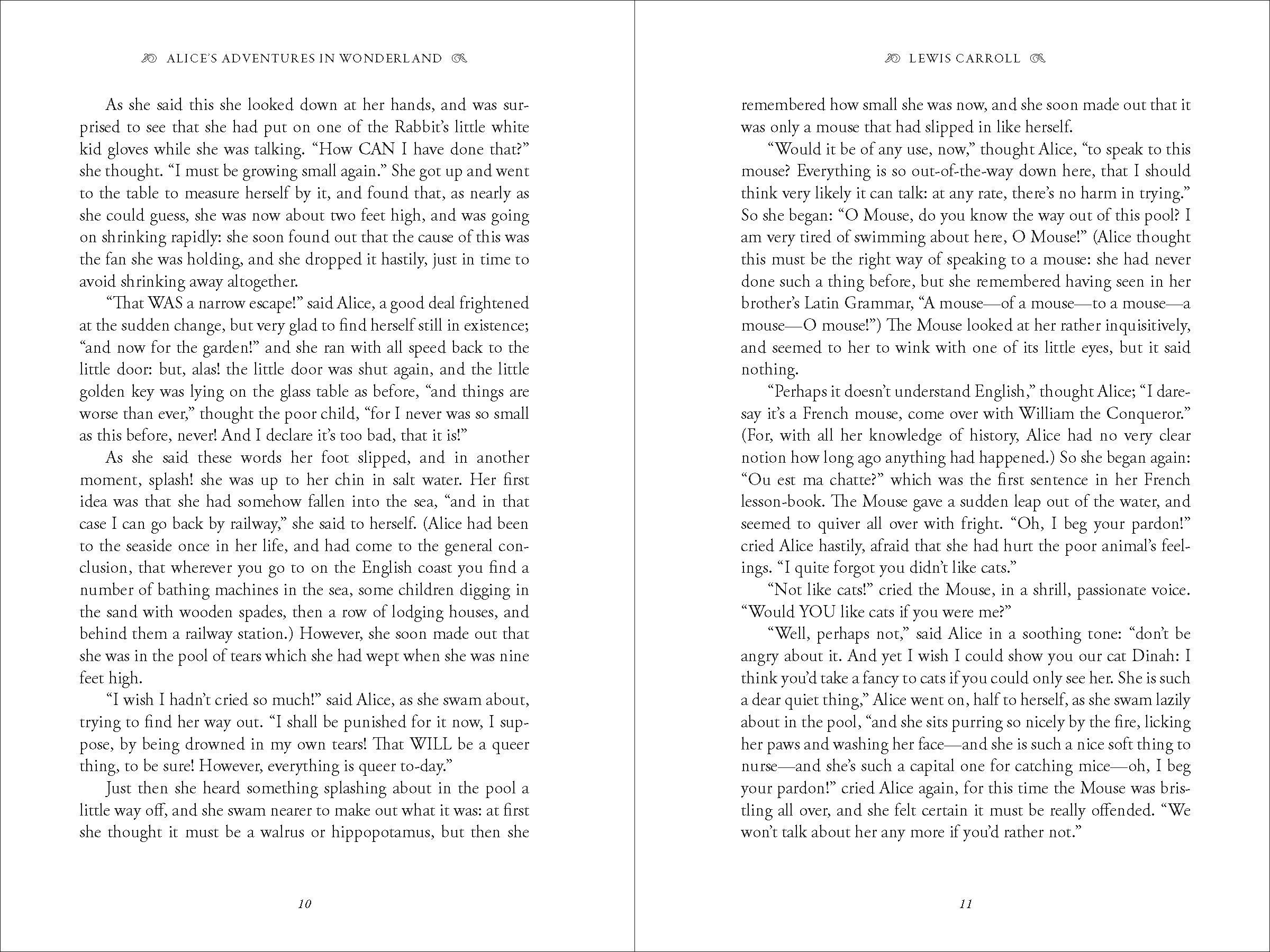

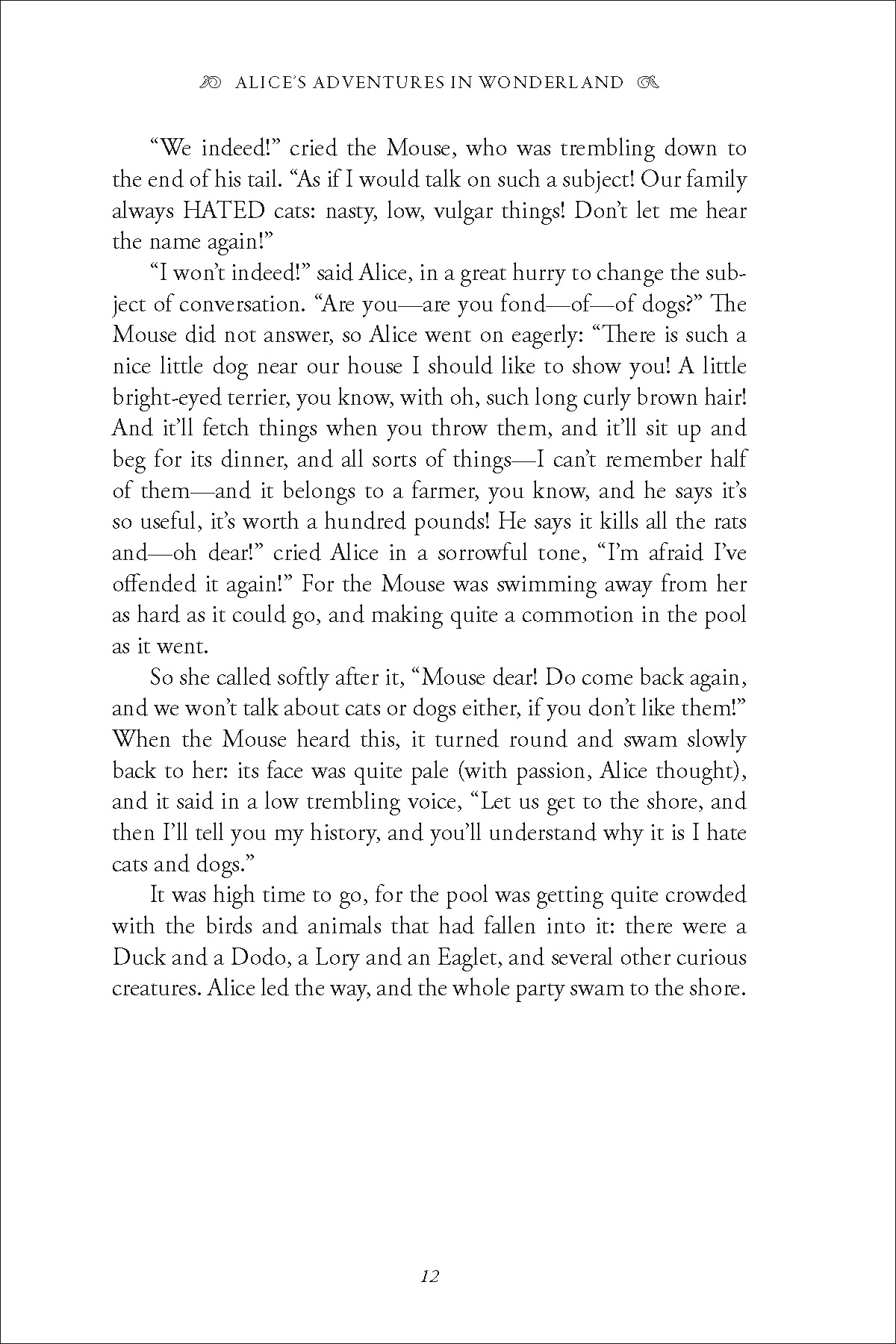

body: the main text

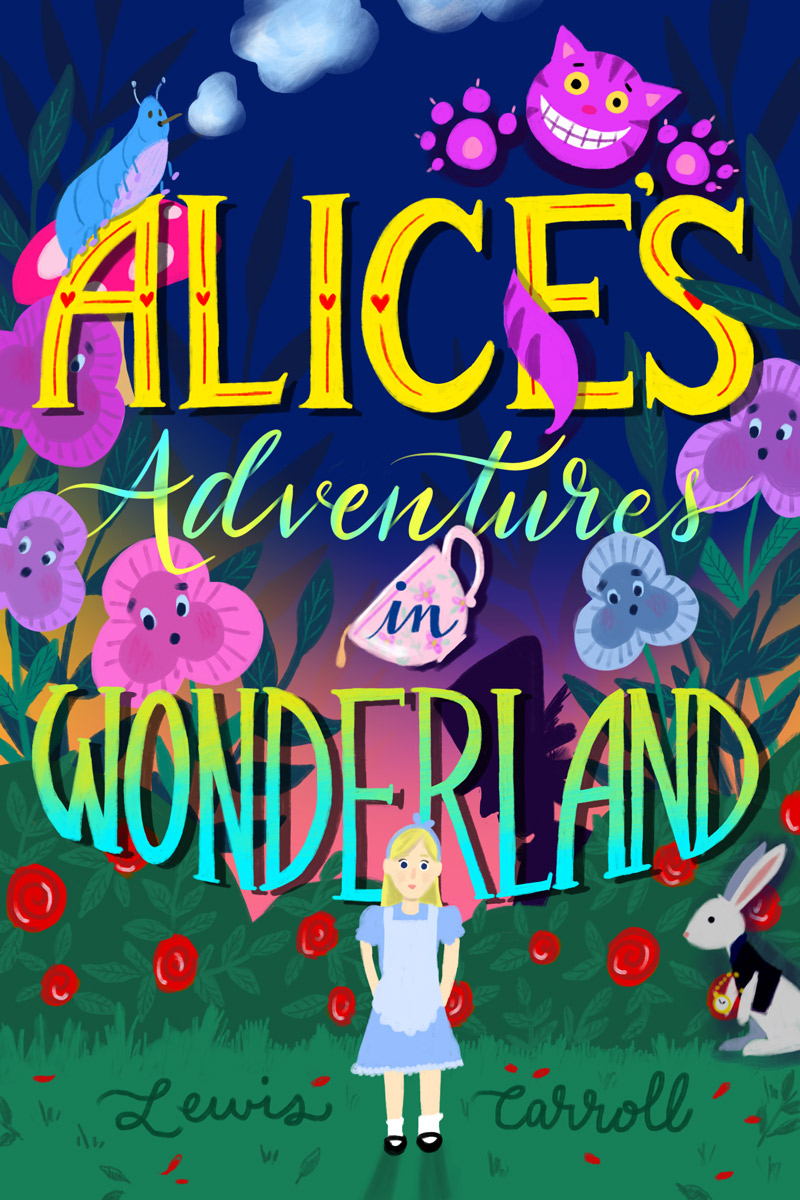

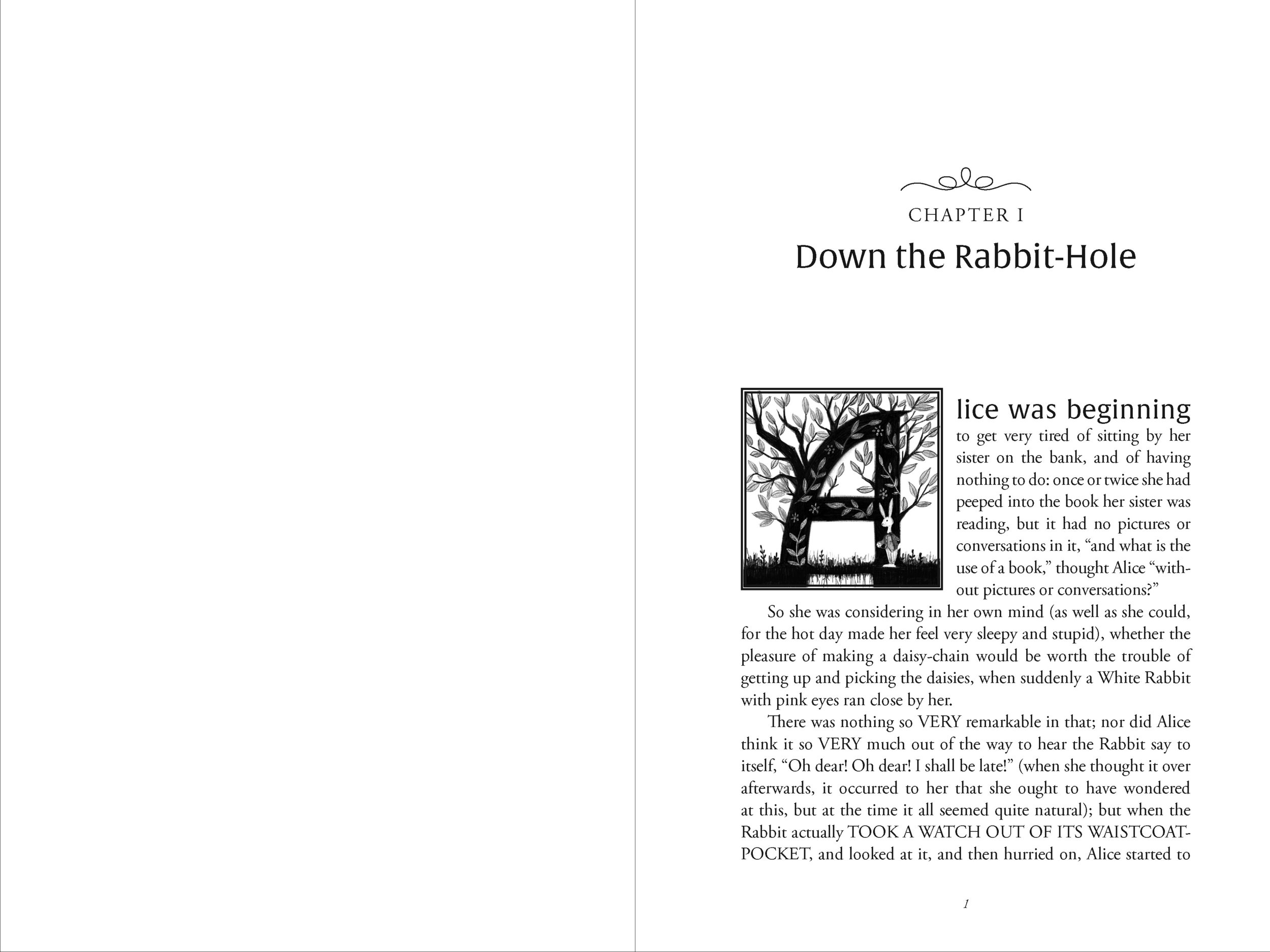

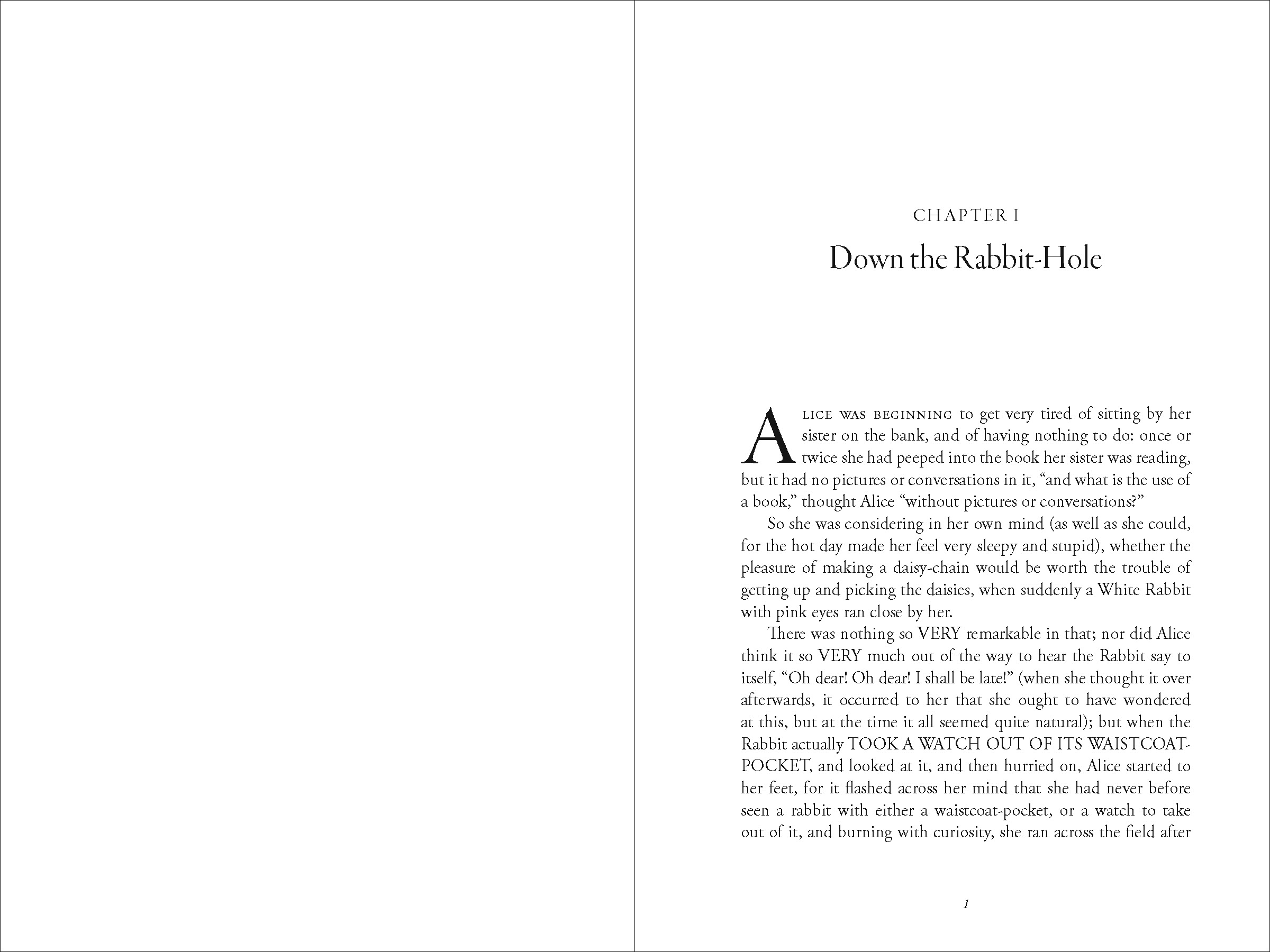

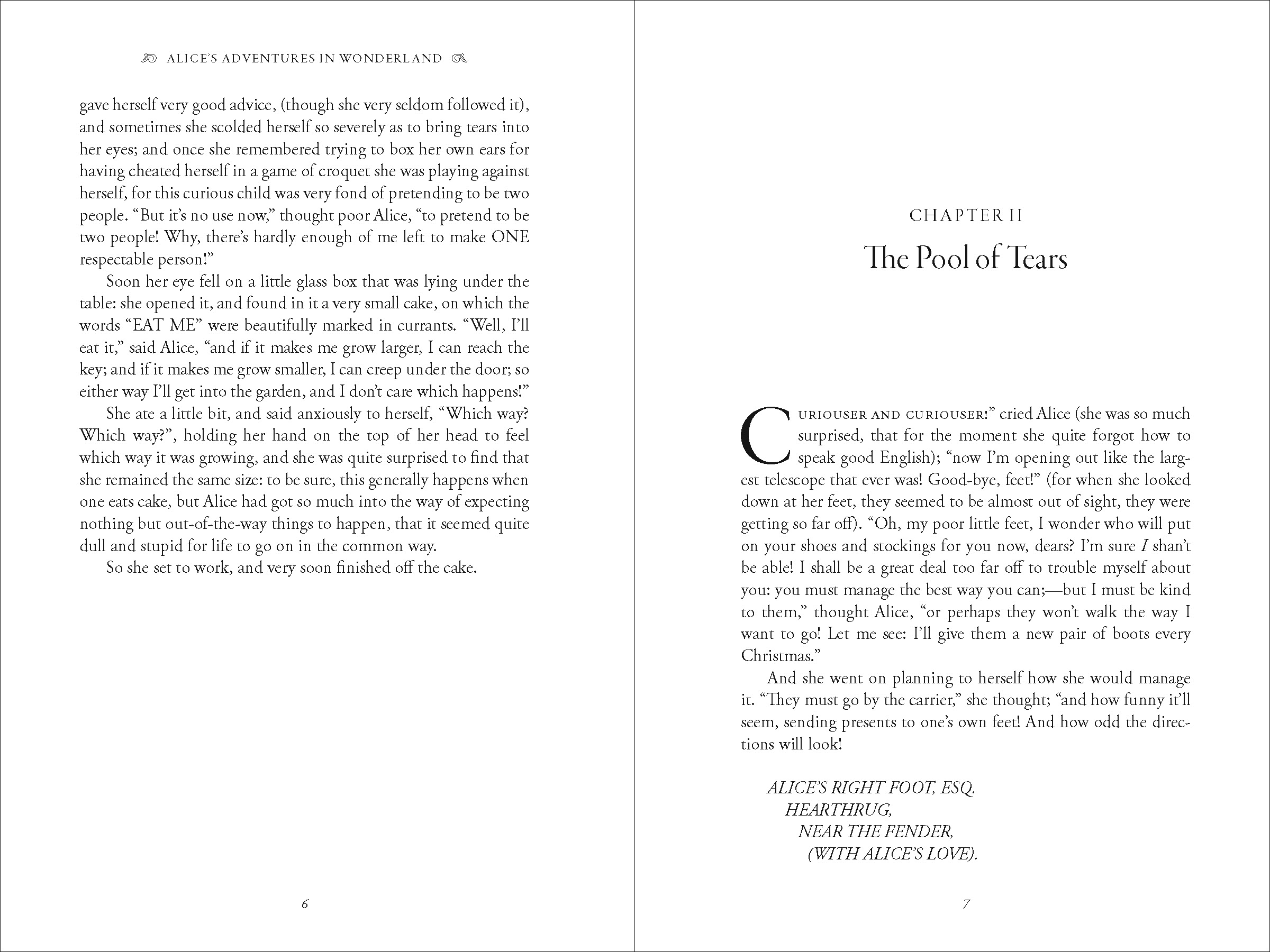

display fonts: special fonts that differentiate from the main text and add design flair; used in headings, title page, sidebars, etc.

text block: the area on the page taken up by text

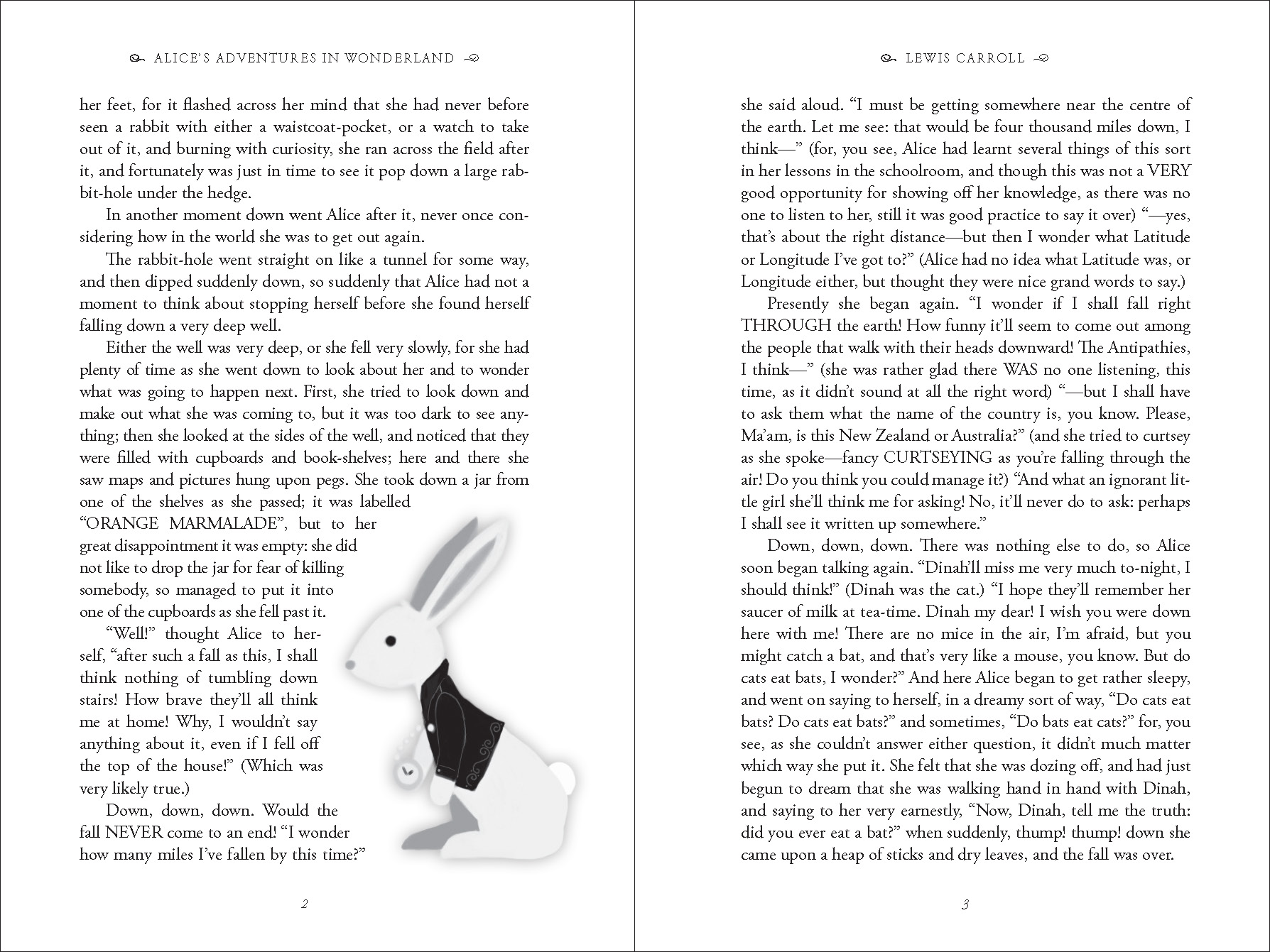

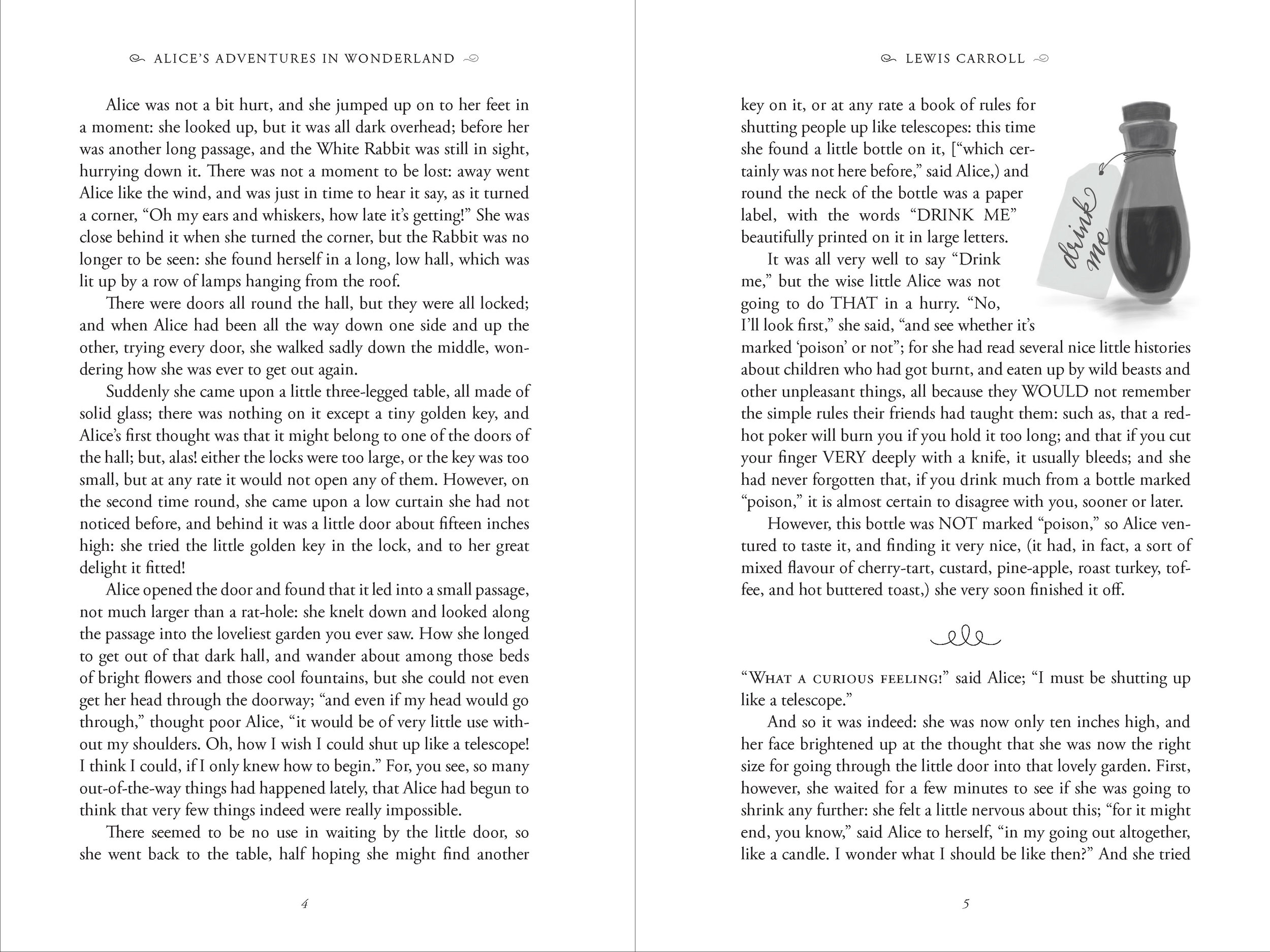

running head: text heading that runs on the top of each text page; usually contains info such as the book title, part or chapter titles, and/or the author's name

running foot: similar to the running head, but is found at the bottom of the page

folio: page number; this can be found at the top or bottom of the page, sometimes aligned with the running head or foot, if there is one; at the bottom of the page, it can be referred to as a "drop folio"

form or signature: Traditionally, books have been printed in multiples of 8 or 16 pages, which equals one signature. This has to do with the way the large sheets of paper are cut and sewn together to create the book pages. Whether a book's page count is required to fall on an even signature depends on the printer being used. Many digital POD sites like Createspace only need an even number of pages, however.

frontmatter: pages at the beginning of the book before the main content; usually comprised of the title page, copyright, dedication, foreword, and/or table of contents

backmatter: pages at the end of the book that aren't a part of the main content; usually includes things like the index, glossary, about the author, acknowledgments, and bibliography

spread: comprised of two pages (one left, one right) that fall side-by-side

recto: right-hand page

verso: left-hand page

Tips for Good Page Design

Perhaps you've never even noticed these things before, but I think you'll find that your page layouts will look a lot better by paying attention to these general rules...

Gutter: The gutter margin is often set wider than the outer margin. This is to compensate for the page space that is lost in the binding. The general rule is that higher page counts need larger gutter margins. Lower page counts (such as in picture books) don't necessarily need a larger gutter.

Typography: Keep the number of fonts to a minimum—usually 2 or 3. That's a good rule of thumb for ANY design project. I often have a main body font (usually serif), a display font (a contrasting typeface that fits the mood of the book), and, occasionally, a secondary text font (sans serif) for things like sidebars, callouts, and tables.

Blank space: Part of being a good designer is knowing when NOT to fill a space. Sometimes white area is ok, and will make your design look better. Some examples of where you could use white space are the above headings, around illustrations, "sinks" on your chapter opener pages (see diagram), or adding blank left-hand pages so your chapters and/or sections always start on a right-hand page. (Blank right-hand pages, however, are usually a no-no.) Also be sure to give your main body text some breathing room by using enough leading (space between lines). I generally set my leading at least 2 or 3 points above the font point size.

The fine details: There are several ways you can fine-tune your composition. Here are a few things to look out for that we often try to AVOID in publishing:

- stacks - when the same word ends or begins two or more lines in a row; usually two lines are considered ok, but three or more stands out

- widows - starting a page with a single line from the end of a paragraph

- orphans - when a paragraph ends with a short word; it's best to end with a word or words that are longer than the width of the paragraph indent

- 2-down hyphenation - allowing words to hyphenate with only two letters on the following line. Three or more letters are better.

- loose/tight lines - just as it sounds—when the spacing of the words and letters looks too spaced out or compressed

Many of these issues can be fixed by learning to use composition features in your page layout software (i.e., H&Js, Keep Options, Tracking, etc.), and some require manual tweaking. With that in mind...

Use software specifically made for page layout to compose your book. By this, I do NOT mean Microsoft Word. Adobe Indesign is by far the most widely-used program and an industry standard. (A common alternative is Quark Xpress.) Yes, it is pricey and not for the casual user. If you are serious about diving into book design, Indesign is the way to go. There are cheap or free alternatives out there. But, seriously, use Indesign.

This is all just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to designing book interiors. I know I've learned a lot since I first started out, when I knew pretty much nothing. I think book design is something that might appear simple on the surface, but becomes overwhelming once you realize how much goes into it. Like anything, it takes a bit of work, practice, and experience.

When in doubt—there's always the option to hire a pro! ;)

I hope you've at least learned something new about book design today and can appreciate the process.

Sincerely, Nicole

Links

My Journey into Book Design